It's the Christmas holiday and Katie and I are in Hawaii spending time with her son and his family. Hawaii is the only place in the US that feels like a foreign country, an Asian country to be more precise. When I started writing this blog entry, it was Christmas eve and we were sitting in the food court at Ala Moana Center in Honolulu, at a table adjacent to the Kansai Yamato Mochi stand. It's very crowded here at the mall and there's a line of people at the stand. In the display case, arranged in neat rows, are pink, green and white round, plump mochi cakes. Mochi is pounded sweet rice. It is extremely chewy and eaten as a snack or dessert. Some of the cakes have a toasted coating, some are filled with sweet bean paste and some have no filling at all. I can't think of an equivalent food from my mid-west background. At a time when I might eat a cream cheese Danish, a Japanese person would eat a mochi cake. I don't think a mochi stand would survive very long in Green Valley, Az. where we live, but Katie would love it if one tried.

When I was in Vietnam in Army Intelligence, I worked closely with Vietnamese interpreters and spent my tour of duty questioning Vietnamese people, soldiers and civilians. Ever since that time I have felt comfortable around Asian cultures in general. During the TET celebration of 1968, before all hell broke lose, an interpreter named Tan invited me to his family's home for the holiday dinner. His was not a family that could afford feeding guests. In spite of this, they managed to put out an elaborate spread of food, much of it I didn't recognize. I was 20 years old at the time and the only Asian food I'd eaten previously was canned Chun King chow mein. I remember especially liking the crispy noodles that came in a separate can. I didn't see any these crispy noodles at Tan's family celebration, but I made up my mind that I would accept and eat graciously whatever was served. To my surprise the food was delicious. Later, Tan told me what some of the foods were and I was glad he hadn't told me ahead of time. One of the dishes I remember was peanuts in ducks' blood. I thought of it as a yummy dish with a dark tangy sauce. While we were enjoying the meal, I noticed another full set of serving dishes over to the side that nobody touched. Tan told me that that food was for their dead ancestors. I wondered whether the family would eventually eat this food, or throw it away, but I never found out. Christmas in Hawaii is also about getting together with family and friends and eating a lot of carefully prepared delicious food. I guess that's really no different from anywhere else.

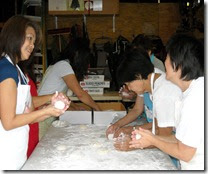

Our daughter-in-law is Japanese, and she invited us to participate in one of her family's holiday traditions, making mochi the old fashioned way.When we arrived at her cousin’s house, the process was already underway. It was all taking place outside the house on the driveway and in an open two car garage. After being introduced around, I stood and watched for a while. The men handled the activities on the driveway and the women stood in the garage facing each other across tables. In the corner of the driveway, close to the house was a stack of wooden rice steamers over a heat source. In the center of the driveway was a large stone bowl. One of the men grabbed the top rice steamer and with help poured the softened, cooked rice into the bowl. Some of the women, including our daughter-in-law, had soaked the rice over several nights and now it had been steaming for I don't know how long. Three men or boys then started to mash the rice with wooden sticks. This is the most tedious part and even our 6-year- old grandson, Christopher, was even allowed to do this. This took about 5 to 10 minutes and was the most tiring part of the whole process. One of the older men kept checking to see if the rice granules were broken down enough. When given the OK, the rice mashers stepped aside and another man, wielding a large wooden mallet, began to rhythmically pound the rice. The pounding seemed to be the centerpiece of the mochi making process and the part that transformed the sticky mass into a rubberier substance. Everyone stopped to watch. The mallet was heavy and needed to come down with force and accuracy. Between each pound, another man moistened and turned the ever-thickening batch. When the glutinous product was ready, it was placed on the table where the women are standing. Each time this was done, the women commented on the look and feel of that particular batch. Now the forming of the mochi cakes began.

This is the most tedious part and even our 6-year- old grandson, Christopher, was even allowed to do this. This took about 5 to 10 minutes and was the most tiring part of the whole process. One of the older men kept checking to see if the rice granules were broken down enough. When given the OK, the rice mashers stepped aside and another man, wielding a large wooden mallet, began to rhythmically pound the rice. The pounding seemed to be the centerpiece of the mochi making process and the part that transformed the sticky mass into a rubberier substance. Everyone stopped to watch. The mallet was heavy and needed to come down with force and accuracy. Between each pound, another man moistened and turned the ever-thickening batch. When the glutinous product was ready, it was placed on the table where the women are standing. Each time this was done, the women commented on the look and feel of that particular batch. Now the forming of the mochi cakes began.

The women worked quickly with skilled hands. Before long there were several boxes filled with perfectly round, plump mochi cakes. This whole process continued all morning.

The women worked quickly with skilled hands. Before long there were several boxes filled with perfectly round, plump mochi cakes. This whole process continued all morning.

I got an opportunity to participate in most aspects of the process. I started off mashing. The least skilled part, the grunt work. After mashing several batches, one of the men asked if I wanted a turn pounding. I had entered the holy grail of the process, the only part with spectators. On my second turn at pounding, I thought I was beginning to get the hang of it. One of the older men complimented me on my pounding technique. After working up a considerable sweat with the men, I asked the women if I could join them. They graciously made room for me at the table. Having worked as a baker years ago, it was somewhat familiar territory. I even received a few nods of approval at some of my finished products. I realized however that my mochi cakes weren't as smooth as the others and took me a lot longer to make.

I recently looked up a mochi recipe on the internet. It starts with rice flour and the cooking is done in the microwave. It only takes minutes from start to finish. What a difference from the process I had participated in. There is even a mochi machine, like a bread maker. It's all done automatically; you just add the ingredients. But the process Katie and I participated in wasn't about making the family's mochi. I witnessed this extended Japanese American family contentedly talking and laughing through an extremely labor-intensive, time-consuming process. This is something they do every year and something their mothers and fathers, uncles and aunts who are long gone did as well. Like Tan’s family, this family set aside some of the food for altars on New Year’s Eve. In both cases I had no doubt that the ancestors were right there, celebrating the occasion through the eyes of their children’s, children's, children, just as they'd done for centuries.

This is the most tedious part and even our 6-year- old grandson, Christopher, was even allowed to do this. This took about 5 to 10 minutes and was the most tiring part of the whole process. One of the older men kept checking to see if the rice granules were broken down enough. When given the OK, the rice mashers stepped aside and another man, wielding a large wooden mallet, began to rhythmically pound the rice. The pounding seemed to be the centerpiece of the mochi making process and the part that transformed the sticky mass into a rubberier substance. Everyone stopped to watch. The mallet was heavy and needed to come down with force and accuracy. Between each pound, another man moistened and turned the ever-thickening batch. When the glutinous product was ready, it was placed on the table where the women are standing. Each time this was done, the women commented on the look and feel of that particular batch. Now the forming of the mochi cakes began.

This is the most tedious part and even our 6-year- old grandson, Christopher, was even allowed to do this. This took about 5 to 10 minutes and was the most tiring part of the whole process. One of the older men kept checking to see if the rice granules were broken down enough. When given the OK, the rice mashers stepped aside and another man, wielding a large wooden mallet, began to rhythmically pound the rice. The pounding seemed to be the centerpiece of the mochi making process and the part that transformed the sticky mass into a rubberier substance. Everyone stopped to watch. The mallet was heavy and needed to come down with force and accuracy. Between each pound, another man moistened and turned the ever-thickening batch. When the glutinous product was ready, it was placed on the table where the women are standing. Each time this was done, the women commented on the look and feel of that particular batch. Now the forming of the mochi cakes began.  The women worked quickly with skilled hands. Before long there were several boxes filled with perfectly round, plump mochi cakes. This whole process continued all morning.

The women worked quickly with skilled hands. Before long there were several boxes filled with perfectly round, plump mochi cakes. This whole process continued all morning. I got an opportunity to participate in most aspects of the process. I started off mashing. The least skilled part, the grunt work. After mashing several batches, one of the men asked if I wanted a turn pounding. I had entered the holy grail of the process, the only part with spectators. On my second turn at pounding, I thought I was beginning to get the hang of it. One of the older men complimented me on my pounding technique. After working up a considerable sweat with the men, I asked the women if I could join them. They graciously made room for me at the table. Having worked as a baker years ago, it was somewhat familiar territory. I even received a few nods of approval at some of my finished products. I realized however that my mochi cakes weren't as smooth as the others and took me a lot longer to make.

I recently looked up a mochi recipe on the internet. It starts with rice flour and the cooking is done in the microwave. It only takes minutes from start to finish. What a difference from the process I had participated in. There is even a mochi machine, like a bread maker. It's all done automatically; you just add the ingredients. But the process Katie and I participated in wasn't about making the family's mochi. I witnessed this extended Japanese American family contentedly talking and laughing through an extremely labor-intensive, time-consuming process. This is something they do every year and something their mothers and fathers, uncles and aunts who are long gone did as well. Like Tan’s family, this family set aside some of the food for altars on New Year’s Eve. In both cases I had no doubt that the ancestors were right there, celebrating the occasion through the eyes of their children’s, children's, children, just as they'd done for centuries.

No comments:

Post a Comment